Design Activists

Design Activism

What is Design? What is the role of designers? Who are also individuals and consumers? And how do individuals collectively affect society? These have been some of the questions shaping our concepts and ideas. We, a group of designers, working under the title “Design Activism”, through discussions and exchange of concerns on human-centered consumption and current manufacturing practices have come to realize that the garment industry today has only been pushing lazy aesthetic trends that support more consumption. It is a fact that we are deeply submerged in the vicious cycle of “Making Something New” or “Return of the New” that we have lost sight of what our roles or contributions should be to our society and environment. These thoughts led us to dive deeper into the issues and collect information on the real facts behind our concerns.

During this project, our discussions revolved around mending and repairing and we decided to use our exhibition as a platform to promote the “mending culture”. Mending and repairing have historic burden of showcasing poverty, which is quite deeply rooted in our society. Shiny and new resonates with monetary wealth while fixing reflect lower social status and position. In the socio-economic situation, where we can afford more new things, it is more convenient (and socially applicable) to prefer new to old. On the other hand, mending is one of the easiest ways to prolong the garment’s lifespan and thus create a stronger emotional attachment with the piece. Of course, as there are many barriers, why not repair (lack of time and knowledge, social stigma, associating with “women’s work”), how to make it more attractive and engaging to people, who are not so aware of the practice’s benefits?

Despite many negative connotations, repairing is a form of ‘rebellion’ by hacking the closed nature of clothes. By mending, greater emotional connections with mass-produced clothes are fostered. Additionally, repairs are a creative medium, treated as ‘badges of honor’, reflecting the pride of being a repairer than product’s downgrade. How the mendings are done is up to the user and therefore medium for making garments more personal.

However, mending as a skill is slowly fading, so we are working on turning “vending machines to mending machines” and “first aid stations to emergency repair stations for clothing”. Part of our concept is to set up a station where people can make their own customized repair kits to carry with them, this engaging and interactive activity would encourage them to adopt the “I fixed it” trend. Instead of providing “ready” repair kits, in the ‘mending machine’ we provide basic tools, equipment, and materials, so all could take what they need instead of simultaneously overconsuming.

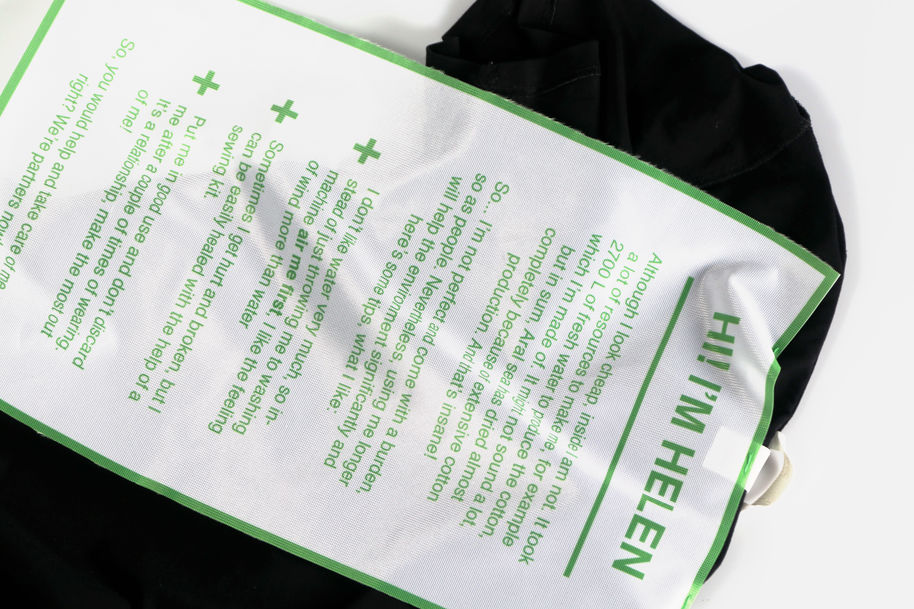

In addition to the repair kits, we have made labels, which highlight the story of garment and the challenges it faced during construction. Helen is the name of a basic T-shirt, which has a bit of a background, but it wants love and affection from its owner. As T-shirts are one of the most ‘unvalued’ garments, they have a significant environmental impact – as soon as they start to become worn-out, they’ll be replaced. So we felt that as purchasing cheaper T-shirts can be often inevitable, then instead of blaming people for making the purchase, we’d highlight its background and give tips for better maintenance. On the labels, we shared bits from Helen’s background and wrote how it likes to be taken care of. By doing so we want to give garments a sense of emotional value. We believe that humans have a tendency to value material items more if there are some emotional connections associated with them, so we are incorporating the same method in our project. All the labels are available in mending machines.

Our aim has been from the beginning to take the discussions outside the university. The academic environment is full of people who know the dark side of the fashion/textile industry, but there are not many discussions outside the safe bubble. Fast fashion chains are still growing and it’s difficult to make people not to shop there, as the cheap prices are seductive. Our idea is to promote repairing as a positive phenomenon and a simple way of maximizing existing garments. So instead of just sitting and waiting for the change, we became design activists! Join us by assembling your own emergency sewing kit, take Helen labels and attach them at the store to T-shirt care label to raise awareness and make the change!

Group members:

Xiao Li, Inka Ikävalko, Ushnah Amjad, Triin Tint

References:

Chapman, Jonathan. 2005. Emotionally Durable Design: Objects, Experiences, and Empathy. London: Earthscan.

Drew, Deborah, Reichart, Elizabeth. 2019. “By the numbers: the economic, social and environmental impacts of 'fast fashion’.” Published January 17. Article. https://www.greenbiz.com/article/numbers-economic-social-and-environmental-impacts-fast-fashion

Hurst, Nathan. 2017. “What’s the Environmental Footprint of a T-Shirt?.” Published April 12 at smithsonian.com. Article. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/whats-environmental-footprint-t-shirt-180962885/

Gill, Alison, and Mellick Lopes, Abby. 2011. “On Wearing: A Critical Framework for Valuing Design's Already Made.” Design and Culture: The Journal of the Design Studies Forum, 3:3, 307-327

McLaren Angharad and McLauchlan Shirley. 2015. “Crafting Sustainable Repairs: Practice-Based Approaches to Extending the Life of Clothes.” Plate Conference 2015 presentation. Accessed October 27, https://www.plateconference.org/crafting-sustainable-repairs-practice-based-approaches-extending-life-clothes/

Sustain Your Style. n.d. “Fashion's Environmental Impact”. Article. Accessed October 27, 2019. https://www.sustainyourstyle.org/old-environmental-impacts (Sustain Your Style, n.d.)