Teuvo Kohonen in memoriam

Academician of Science, Professor Teuvo Kohonen (1934–2021) has passed away. Kohonen was a pioneer of research and education in information technology. His work on neural networks received global acknowledgement.

Artificial intelligence applications have become part of everyday life also here in Finland. AI solutions are utilised in customer service, marketing, medical research and industrial processes alike.

But each step forward in AI needs to be backed by extensive research. In addition to strong ongoing research, Finland’s advantage in the building of better artificial intelligences includes an exceptional history. One of the world’s key pioneers in AI research was none other than Helsinki University of Technology Professor Teuvo Kohonen (1934–2021).

The January 1982 issue of Biological Cybernetics marked a turning point in the history of Finnish research. The scientific journal, which focuses on research in self-steering systems, published an article titled Self-Organized Formation of Topologically Correct Feature Maps by Professor Kohonen.

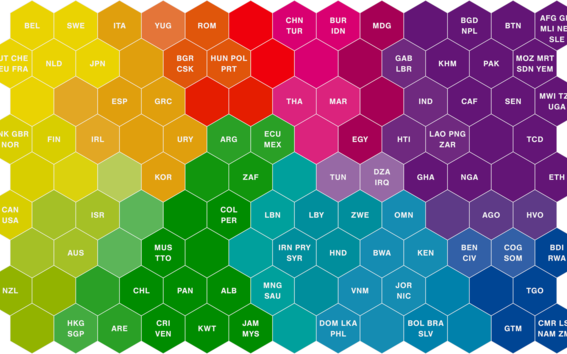

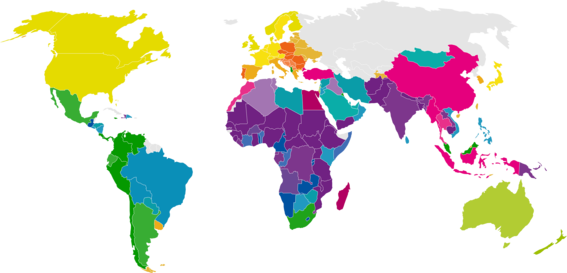

Kohonen’s paper described a novel method for organising complex material into a two-dimensional map in a way that groups sets containing similar features close to one another. The similarities and differences contained in the material are shown as distances between points on the map.

Kohonen referred to his algorithm as a self-organising map (SOM) and his 11-page paper went on to become one of the most significant and cited Finnish research articles of its time.

A former student of Kohonen and a member of his research group, Professor Emeritus of Computer Science Erkki Oja, describes the map as a great invention that opened up a key field of neural computation research.

‘Today, it serves as a typical example of research in unsupervised learning,’ Oja says.

When Kohonen penned his article for Biological Cybernetics, the research community was divided into two competing factions on the question of modelling thought processes computationally.

Supporters of so-called classical symbolic AI believed that mental operations could be best modelled by using logical rules and relations created for the system.

The neural computation camp, which Kohonen belonged to, held the view that the problem should be approached through collaborative action between computational units referred to as neurons.

Oja says that Kohonen was inspired by how the human brain processed information and at first considered the associative memory model, which refers to the capacity to recognize the dataset being searched based on its constituent parts and resembles human memory. Kohonen soon found a more effective direction in a categorisation method referred to as pattern recognition.

‘Kohonen realised that memory does not work like a computer. It’s an impossible idea because of the technology in a computer,’ Oja says.

Finnish Center for Artificial Intelligence Director, Professor Samuel Kaski‘Finland is now home to very significant AI research, also on the global scale.’

A self-organising map starts off with a dataset, which is fed into the system in numerical form. Artificial neurons learn through repetition of an algorithm to independently classify the input’s different properties without knowing the correct answer beforehand.

Oja remembers how Kohonen emphasised that the algorithms should be tested as realistically as possible, using authentic materials. The first practical applications of the self-organising map focused on speech recognition. Sound spectre recordings of speech some ten milliseconds long were used as input.

Helsinki University of Technology’s Neural Network Research Centre, which was led by Kohonen, also developed the WebSom method that utilises the idea of the self-organising map for the purposes of organising and searching digital texts. It creates a visual representation from text material in which texts that are similar in terms of content are placed in each other’s proximity.

‘WebSom did a lot to make Kohonen a recognised name. It was one of the first really big neural network applications.’

Over time, the self-organising map accumulated thousands of research citations as well as a large selection of practical applications. Kohonen’s invention was applied to analysing large data volumes in fields ranging from chemistry to communications technology and from medical science to the process industry.

Oja says Kohonen realised quite early that the global volume of data was about to undergo explosive growth. This was still a novel idea in the computer science of the early 1980s.

‘Neural networks are popular precisely because they make the handling of massive datasets possible.’

Oja remembers Kohonen as not only a brilliant researcher, but also a demanding personality who took scientific work very seriously indeed. His point of departure was that the research problem should always be on your mind.

‘If you’re engaged in scientific work, then do it seriously, Kohonen emphasised. Think about it all day, even in your sleep,’ Oja says.

Kohonen also observed these principles in his own life. He published his final textbook, which is crammed with scientific and technical calculation examples written in the MATLAB language, in 2014, the year he turned 80. The book focuses on using the self-organising map in the MATLAB computing environment.

Deep learning neural networks and other AI methods surpassed Kohonen’s map after the turn of the millennium, but the SOM still pops up from time to time as a data organising and visualisation tool in research papers from a variety of fields.

The mark left by Kohonen is still felt in domestic science circles, says Professor and Finnish Center for Artificial Intelligence Director, Samuel Kaski, who studied the self-organising map in his doctoral thesis.

First and foremost, Kaski characterises Kohonen as a scientific innovator who had strong faith in his own views. At the same time, he demonstrated that Finland can produce pioneering research in the field of artificial intelligence as well.

‘This is precisely what I myself found enticing. I wanted to learn from a person who was engaged in pioneering work,’ Kaski says.

Retrospectively, it is easy to say that the success of Kohonen played a part in cementing the strong role of AI as a research field at Finnish universities.

‘Finland is now home to very significant AI research, also on the global scale.’

Academician, Doctor of Technology Teuvo Kohonen (1934–2021) was a pioneer of computer science research and education. Kohonen is one of the internationally best-known neural network researchers. He was awarded the title of Academician in 2000.

Text: Panu Räty

This article has been published in the Aalto University Magazine issue 30 (issuu.com), April 2022.

Academician of Science, Professor Teuvo Kohonen (1934–2021) has passed away. Kohonen was a pioneer of research and education in information technology. His work on neural networks received global acknowledgement.

Breaking Ground is an exhibition which highlight the interconnected histories of long term and fundamental research and their impact on society