Campus as a testing ground for soil improvements

Vegetation and soil form a related whole. Earthworms, nematodes, organic matter, and other organisms maintain the microbiological balance of the soil. The soil's pH level, the balance of nutrients, the amount of organic matter, and soil granularity determine what type of plant species the soil can support in natural environments. This affects which species succeed in the competition for space when the soil is barren and nutrient-poor, or alternatively, rich and fertile.

Plant communities are often connected to the surrounding trees, which influence the composition of the undergrowth vegetation. For example, hazel bushes on campus produce nutrient-rich loamy soil, which often supports demanding deciduous species. Pine trees, on the other hand, indicate a site with lower nutrient levels. Their root areas typically feature heath vegetation and plants that have adapted to low nutrient and water availability.

Examples of barren habitats on campus include Marsio's nutrient-poor natural meadow, the sunny habitats established with seedlings and seeds of native wild plants in front of Dipoli, and the vegetation in the atrium courtyard of Otakaari 1. The forest surrounding the Alusta Pavilion and other plant species indicate a more fertile soil.

The microbiological network in the soil recycles nutrients for plant use. Nutrients need to be in a form accessible to plants for plant communities to thrive in extreme climate conditions. Plants require healthy and functional soil to obtain nutrients in the right form, and a healthy soil's water retention capacity helps to prevent surface runoff of stormwater.

Experiments in the amphitheatre area

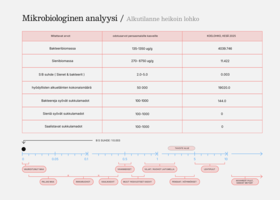

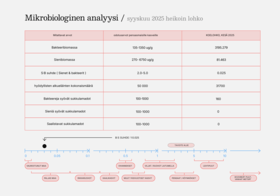

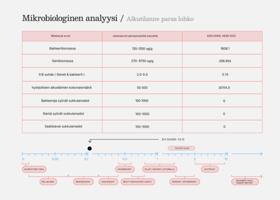

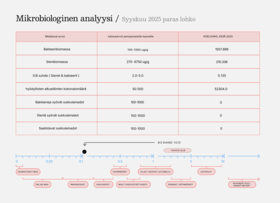

The functionality of the soil can be improved by several methods, which have been experimented with on campus, including the perennial plantings in the amphitheatre area. At the amphitheatre, soil growth conditions have been ensured using three different experimental methods: compost slurry sprays on plant foliage, compost with well-decomposed wood chips as surface mulch, and soil inoculation. The aim is to use test plots and control plots to determine which method would be the most effective for improving growth conditions in other areas as well. Results from the substrates restored with a research-based approach became available in the fall of 2025 (below in Finnish).

Biochar and mycorrhiza as rehabilitation methods

The campus has also employed other spontaneous soil rehabilitation methods, where results are monitored through visual observations. One such method has been the addition of biochar to the substrate. Biochar sequesters carbon in the soil and gradually releases nutrients for plant use over time. It also provides a large surface area for microbes to thrive. For instance, biochar has been used in the Alusta Pavilion and its plant community's soil.

A healthy microbial community and earthworms ensure the soil functions well, maintaining a loose and nutrient-rich environment where plants can access nutrients and the root zone remains aerated due to the burrows dug by earthworms. Earthworms also fertilize the soil with their castings, which provide plants with nutrients.

In experiments with spontaneous rehabilitation actions, mycorrhizal fungal networks have also been used in some areas. These fungi form a symbiotic relationship with plant roots, receiving carbohydrates from the plant and providing nutrients in return. This exchange allows plants to utilize soil nutrients more efficiently, enhancing both soil and plant water retention capabilities.

This is especially crucial now as climate conditions become increasingly extreme, with prolonged dry periods and intense rainfall events. In such circumstances, poorly functioning soil cannot retain water, causing nutrients to wash away into waterways and depleting the soil. Deciduous and coniferous trees have their own mycorrhizal systems, so understanding and applying the correct measures in using mycorrhiza is essential.