The world on display – World’s fairs as seen through the Aalto University Archives

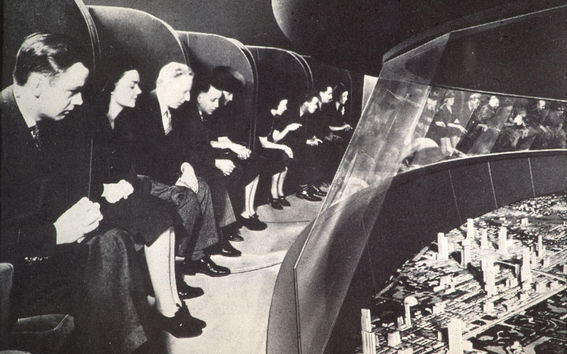

The Universal Exhibitions should be thought of as one of if not the most important events for culture, science and industry all the way from their inception to deep into the 20th century. In fact, the tradition is still very much alive, but thanks to advancements in communications and physical transport, their role is less important by default. In a time before the internet, the world fairs were a very important, international forum for communicating ideas and technological and commercial co-operation in general – essentially fulfilling a somewhat similar role to the internet.

The object of the expos was, supposedly, the world in and of itself and in its entirety. This is a very important part of their appeal, but also an inherent flaw in the concept. The exposition area was typically composed in part of thematic exhibits on topics such as the fine arts or industry, as well as pavilions set up by participating countries, typically presenting aspects of their culture and attempting to advance external perceptions of commercial prospects in their country. While this was an effective way to try and display the world itself, the task was still impossible. It should also be mentioned that there were also things that strictly didn’t belong in the expositions which included any criticisms or questions about the status quo.

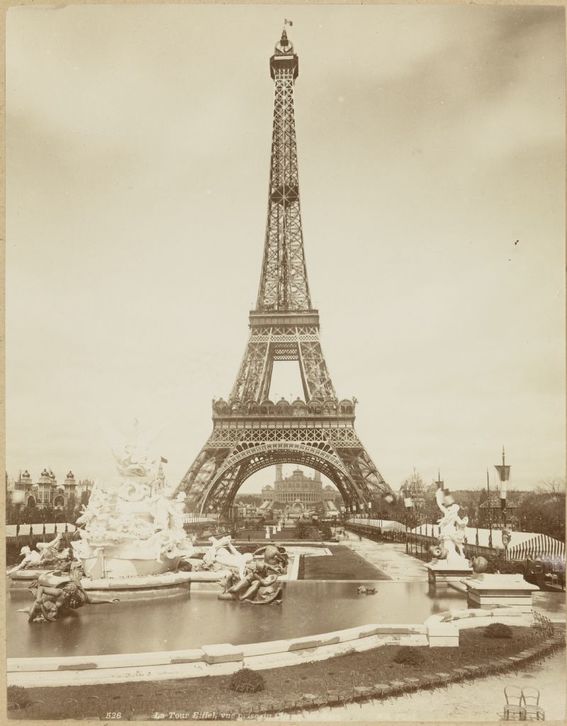

The exposition venue had to be impressive in and of itself. The most well-known example of a building constructed for one of the expositions must be the Eiffel Tower, constructed for the 1889 Paris Exhibition. It is a good example of the general architectural style of the expositions – massive (the highest building in the world until 1930) and very technologically advanced for the time. What’s exceptional about the Eiffel Tower, however, is that it’s still there. Typically, all structures built for the Expositions were supposed to be temporary, and the Eiffel Tower wasn’t supposed to be an exception. The buildings not being permanent allowed for even more expansive, experimental and grandiose construction. Structural integrity in the long term not being a concern allowed for more ambitious projects that would have been otherwise impossible or economically infeasible at the time. In this way, the expos presented a vision of the future.

The Expositions of 19th and early 20th centuries can be thought of as a culmination of enlightenment thought and the myth of progress that stemmed from it. Downright pompous displays of each country’s technological and cultural achievements were the meat and potatoes of the expositions. This particularly applies to “western” countries – countries outside of Europe and North America were included mostly as exotic curiosities. In some cases, colonies of European countries were allowed to set up their own displays, but these were obviously put together by the colonial administrations. Therefore, they included what was considered valuable by the colonial upper class, which could be very different from what was valued by the native populations.

Finland enters the international stage

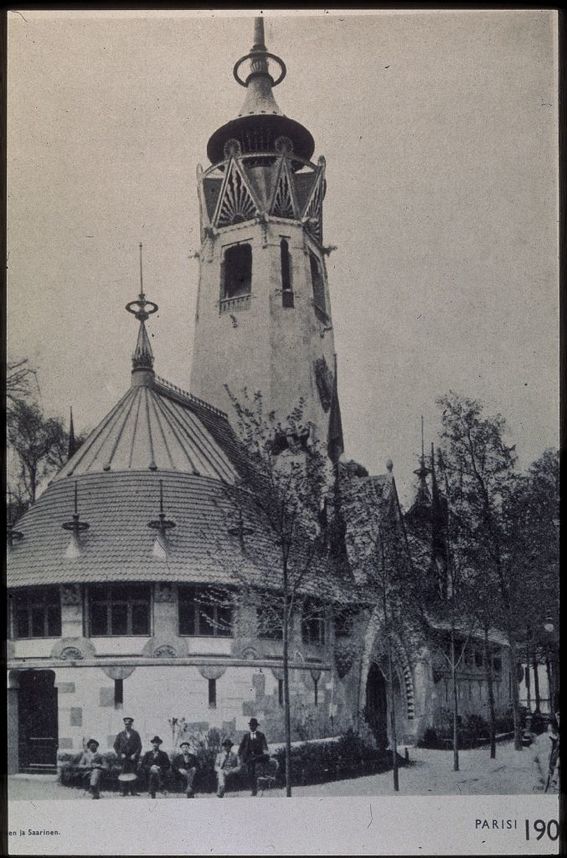

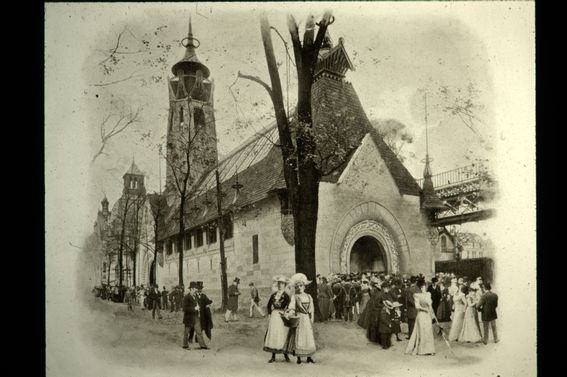

The Grand Duchy of Finland, part of the Russian empire from 1809 to 1917 was allowed to participate in several Expositions as part of the Russian display. In the 1900 Paris exhibition, Finland even got to set up its own pavilion next to the Russian one. It wasn’t by any means unheard of for national entities that were not independent countries to be allowed to set up their own displays. There were several other such cases in the 1900 exhibition as well. The Finnish pavilion was designed with relatively little oversight from the Russian government, the only requirement being to include the two-headed Eagle symbol in the Pavilion’s Tower. Otherwise, the Pavilion was designed in the Finnish national style, which was being invented at the time.

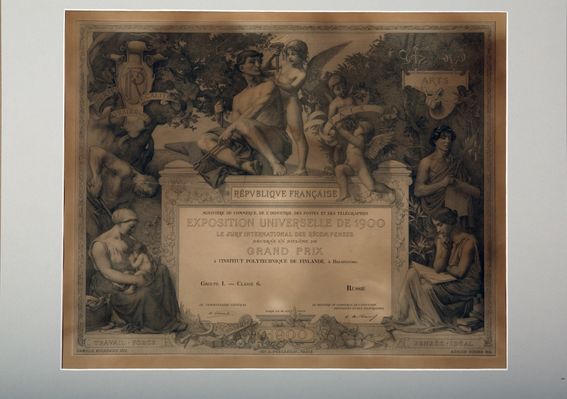

The Polytechnic Institute of Finland earned a Grand Prix at the 1900 Exhibition. The Polytechnic Institute became the Technical University of Finland in 1908 and was then renamed the Helsinki University of Technology (HUT) in 1942. The HUT, in turn was one of the universities that formed the Aalto University in 2010. The Grand Prix diploma can be found in the Aalto University Archives. It’s an interesting piece from an artistic perspective alone, featuring classically inspired characters boasting signs alluding to what were presumably considered core French values (“Liberty, fraternity, equality, peace”).

The Grand Prix was apparently earned for a pair of folders which included architectural drawings and building designs by students. One of the folders includes structural drawings, engineering-oriented technological solutions, in essence. The other one included drawings of facades and floor plans. Both folders are available in the Aalto University Archives.

Some diplomas were also earned by Finnish arts and crafts. In the Aalto University Archives, one can find three diplomas from the 1930 Antwerp expo and six from the 1935 Brussels expo. The 1935 diplomas were granted to particular artists and designers such as Aino and Alvar Aalto (although Aino’s name is misspelled), while the 1930 diplomas were all awarded to Ornamo, a Finnish organization for designers.

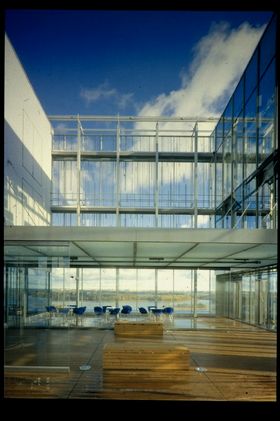

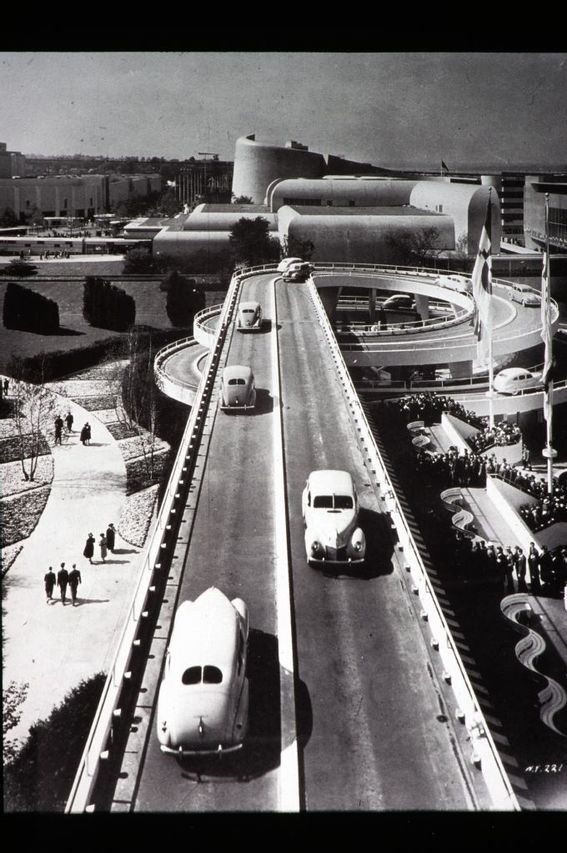

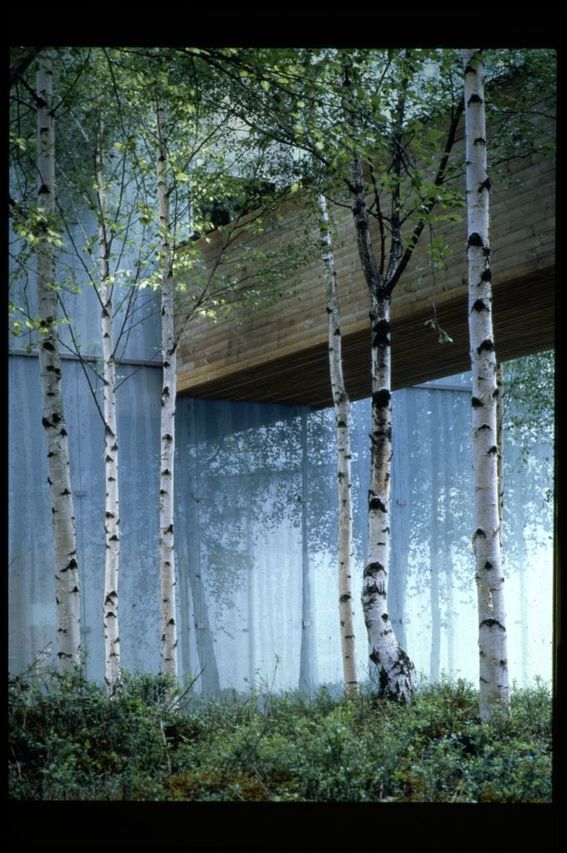

After declaring independence in 1917, Finland continued to participate in the Expositions whenever it was financially possible. The most well-known and positively remembered efforts were 1937 Paris and 1939 New York pavilions, both designed by Alvar Aalto. In 1939 especially, the display included in the pavilion was also largely arranged by Aalto and his wife, Aino. These Expositions played an important role in catapulting the Aaltos’ international career, as well as boosting the image of Finnish architecture and design.

The earlier expos mainly served as events for promoting industry. The idea was largely focused on dazzling the visitors with technological achievements and their practical, industrial applications. By the time Finland became a regular, relevant participant, the expos had become much more focused on culture. Thus, the Finnish Society of Crafts and Design (Suomen Taideteollisuusyhdistys, STTY) as well as the University of Arts and Design Helsinki played a major role in coordinating the materials of the display.

Both of archives are stored in the Aalto University Archive collection and can serve as an important source for research into Finnish participation in the expos. These include many interesting sources, such as annual reports, minutes and letters.

The STTY archive has separate folders for documents related to exhibitions abroad, including the expos. These include correspondence, memos related to exhibit design and other material such as the catalogue for Finland’s compartment in the 1889 Paris Expo. The extent of the material per expo varies heavily, mostly based on the extent of STTY’s role in the exhibits. The documentation is mostly related to the activities of STTY itself.

For example, the 1939 New York folder only includes the program for the pavilion design competition, (which was eventually won by Aalto not in association with the Arts and Crafts Society), whereas the 1937 Paris folder includes a wide variety of correspondence, budget calculations and design-related documents. There is also no mention of expo 1939 in the annual report for the year. The annual report for 1937, on the other hand, includes a couple of paragraphs on the expo, hailing it as a great achievement for Finnish arts and crafts. There is also a mention of challenges related to the coordination process, which is likely referring to artistic differences between Alvar Aalto and Arttu Brummer, who was the art director for the Arts and Crafts Society and oversaw the arts and crafts section of the pavilion. Brummer eventually stepped down from the exhibit design committee altogether. The in-fighting in the committee was also the reason why the design process for the 1939 expo was streamlined, with more control given to Aalto.

There is also a mention of the 1935 Brussels expo in the Arts and Crafts Society’s annual report, which piqued my interest. The Finnish compartment in the expo in question isn’t particularly well-known, but the phrasing used in the annual report provides us with interesting information about how the expos and Finland’s position in the world were perceived:

“On the 10th day of May, Finland’s Pavilion at the Brussels international exhibition was opened. Our compartment’s purpose was mainly to market our country as a destination for travel, alongside which our trade and industrial life’s current level of development was shown through a modest display and statistical visualization material. Attached to the compartment was also a smaller group of arts and crafts products.”

The use of the phrase “level of development” reveals that the writers of the report had to some extent internalized the ideology related to the idea of linear development, where some countries are more developed and therefore better than others. It should be noted that the Finnish word used (kehitysvaihe) carries a heavier moral connotation, than my translation does. On the other hand, the writing is referring to trade and industry in particular, rather than some idea of general development or the kind of explicitly racist development ideology that was very much present in the western world at the time. Proving that Finland was an advanced country seems to be a long-running trend in the expos in general. The 1900 Paris pavilion was apparently made with the explicit (although apparently failed) goal of proving that Finns were not “rough forest folk”, despite of circumstance.

This was not a purely ideological goal of course, since creating an image of Finland as a highly developed country was economically useful in at least two ways. First, this created an image of Finland as a viable trade partner, since Finnish products would be affordable and of decent quality.

Secondly, presenting Finland as culturally advanced would mean that it would be a worthwhile destination for tourists. Access to the comforts of modern life was not obvious at the time, so presenting Finland as a country where they could be guaranteed at least for wealthier tourists visiting larger cities was very useful. A rich cultural life would also mean visitors would have something to do.

While the idea of civilizational development was heavily connected to nationalism, especially from the perspective of participating countries setting up their displays. An example of this would be the goal of “propagating Finland as a civilized country”, which was a stated goal for Paris 1937, according to a memo included in expo’s file in the Arts and Crafts Society’s archives. As the expos in general relied on the concept of a scale of development, on which different participating countries take differing places, a country’s goal would naturally be to show that they are on the higher end of that scale.

The idea of development adapts itself to a new era

Both of the world wars serve as major turning points in the history of the World’s fairs. They were cataclysmic events that obviously disrupted the ideology of progress by showing that technological progress is also a means for great destruction, apparently civilized societies can easily descend into brutal violence and a better life for everyone requires more than technological and industrial development. The societal trauma left by these events seriously complicated the ideology of development.

Rather than inducing a thorough change in the western world view, this only prompted a slight shift in the thinking, where linear positive development was no longer taken for granted. The core idea of humanity becoming better as time moves on and different nations being on different levels, was not abandoned, however.

The 1958 Brussels expo also included a very disturbing, although exceptional only in how late it occurred, example of the outright racist forms the idea of development could take. The Belgian section of the fair featured an exhibit known as the Congolese Village – a so-called human zoo, which featured actual Congolese people hired to live their life under the keen eyes of expo visitors. The Congolese “exhibits” were also treated poorly, with complaints about cramped living conditions and lack of protection against the weather, which was exceptionally cold for the summer. They were not allowed to communicate with the visitors, but the visitors did mock and try to provoke them in various ways. The area was decorated with Congolese-style art that was not actually Congolese, but a European-made stereotypical impression of the style. All of this occurred with the background of severe human rights abuses by the Belgian colonial rule under Leopold II in the Congo.There was also a statue of Leopold II next to the entrance of the exhibit, as if as a final insult.

The Finnish department in the expo obviously didn’t engage in this obviously racist subsection of development discourse. The idea of varying levels of civilization does still appear in the documentation of the exhibit plans. The Arts and Crafts Society played a major role again, so the documentation in their archives is rather extensive. In a report written by Olle Herold, the deputy chief commissioner of the Finnish pavilion, details the general plan for the – namely that it should be mainly ideological in nature, with only secondary consideration given to commercial purposes, although that shouldn’t be forgotten either.

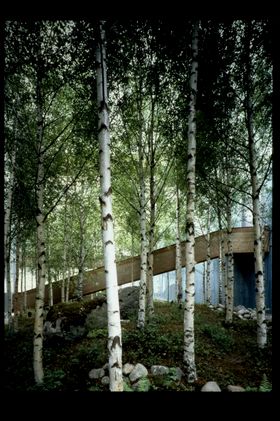

Herold also thought that an ideologically driven exhibition would need to be structured around some kind of theme. The theme he had in mind was Finland's location far in the north, with the goal of showing what that Finland has been “able to achieve a similar level of material and spiritual development of far more advantageously positioned countries”. This calls back to the theme from Finland’s pavilion in the 1900 Paris expo – proving that Finns are civilized folk seems to have been a long-term project.

The correspondence around the 1958 expo is also particularly extensive and would merit a more thorough survey than is possible for this article. It includes circular letters sent to exhibition participants and correspondence with a committee set in co-operation between the Arts and Crafts Society and Ornamo Art and Design Finland. This material could answer interesting questions about Finnish culture at the time – what was considered important about it, who got their works to be displayed, what were the stated reasons and how the selection process was organized. It does not take a very thorough look at the correspondence, however, to see that designers themselves thought it was very important to have their works included in the exhibition, probably for a good reason.

The legacy of the great exhibitions

There is no material related to the Universal Expos after Brussels 1958, apart from some pictures taken during an HUT excursion to the 2000 Hannover expo. There doesn’t seem to be any record of the Arts and Crafts Society contributing to the later expos in any significant way. What is interesting, however is that around the 1970 Osaka expo, in 1969-1971, several articles about previous world’s fairs were released in the society’s yearbooks. There is no mention of the Osaka expo, but it seems that it was expected to increase interest in World’s fairs in general, prompting the release of the article.

These articles are useful documents when it comes to studying how the expos were remembered at the time they were written. The writers do recognize the expos as a vehicle for a competition for prestige between great powers and do go into detail about the political dimensions of the expos. These things are not what the articles are about, however, and the political dimensions are mostly explored from Finland’s point of view. They mostly seek to answer questions about how the Finnish efforts at the Expo came to be.

An article released in 1970 – about the Finnish pavilion in 1970 – even includes a mention of colonialism as a core part of the expos and how the great powers’ colonies were presented. Interestingly, the way the word is used indicates that it doesn’t carry anywhere near the same moral weight it rightfully does today. The colonial exhibits are presented in a way that makes them seem quite harmless, European curiosity and interest towards more remote countries. Of course, it’s not very surprising that attitudes towards colonialism wouldn’t have been particularly critical at the time.

By the time of the 1992 Seville expo the concept of a universal exhibition had changed significantly. In the 1930’s, for example, the usual approach was to create an image of a country’s culture through concrete, sellable products. This relationship between culture and commerce had been reversed – the exhibitions were no longer primarily about exportable products, but about culture itself. This doesn’t mean that the expos were less commercial in nature, only that culture itself became the export. This did exacerbate the paradoxes inherent in the expo concept even further – as culture is not an object to be set on display, except for through incomplete examples and symbols.

The role played by the expos in geopolitics has also been different in past few decades. In the case of the Seville expo, it was no longer perceived as a great achievement by Spain, but more as a desperate effort to revive the country’s struggling economy. Ironically enough, it was clear at the time that Spain could ill afford the expenses of the expo, even after relying heavily on sponsorship from large companies.

Faith in development is still very much alive, although not necessarily very well, today. It seems that built into our culture is still the assumption of a better future – but better as a different version of today – there’s more of everything, it’s bigger and maybe better, but not substantially different. This relationship with the future can be traced back to the 1800’s and the Universal Exhibitions certainly played a major role in constructing this worldview.

Writer: Sander Kööbi

Bibliography

Syrjämaa, Taina. Edistysusko maailmannäyttelyissä 1851–1915. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Helsinki 2007.

Greenhalgh, Paul. Ephemeral Vistas: The Expositions Universelles, Great Exhibitions and World’s Fairs, 1851-1939. Manchester University Press, Manchester 1988.

MacKeith, Peter B.; Smeds, Kerstin: The Finland Pavilions: Finland at the Universal Expositions 1900-1992. Kustannus Oy City, 1993.

Harvey, Penelope: Hybrids of Modernity: Anthropology, the Nation State and the Universal Exhibition. Routledge, Lontoo 1996.

Devos, Rika, Ortenberg, Alexander (toim.): Architecture of Great Exhibitions 1937-1935: Messages of Peace, Images of War. Routledge, New York 2016.

Bruno, Marco: Alvar Aalto: An Anthill Under the Undulating Sky. A Critical View of Finnish Networking. Open house international, 2018, Vol.43 (4), p.80–93

Sotamaa, Yrjö (toim.): Taideteollisuuden muotoja ja murroksia – Taideteollinen korkeakoulu 130 vuotta. Taideteollinen korkeakoulu, Helsinki 1999.