Refashioning the Renaissance Team, Imitation Amber & Imitation Leopard Fur.

Imitation Amber & Imitation Leopard Fur

The “Fake it ‘til you Make It: Imitation in Early Modern Clothes and Accessories” Workshop was organised in early March 2020 by Refashioning postdoctoral research fellow Sophie Pitman, and the whole team was in attendance, plus former Refashioning postdoctoral research fellow Michele Robinson (2018-20) and invited researcher Professor Timothy McCall (Villanova University).

In the sixteenth- and seventeenth centuries, there was a growing market for imitation materials such as fake gold, gems, and pearls, and textiles made out of blended fibres, which could provide a wider population with fashionable clothing and accessories that they could afford to purchase and were legally allowed to wear. Working in the Väre Dye Kitchen and the Biofilia Labs, we tested historic recipes to create imitation damask, add spots to furs, craft pearls from shell or clay, make amber from varnish, and dye fabrics with cheaper dyestuffs. Recipes were selected from Italian, French, and German ‘how-to’ books and manuscripts that were written with increasing frequency from the mid-sixteenth century, appealing to people across the social spectrum who were interested in how natural materials could be transformed and pushed to their limits through artisanal craft.

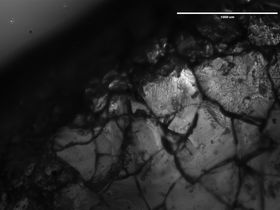

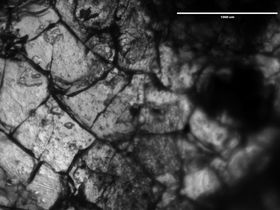

We followed a recipe from the 1595 English translation of Girolamo Ruscelli’s popular Secrets of Alexis Piemontese to make fake amber using turpentine and cotton. We experimented with two types - Venetian Turpentine, and Canada Balsam (which resembles the Strasbourg Fir Balsam used in early modern Europe, that is currently in low supply). As turpentine has a very low flash point, heating it up is a dangerous challenge and so we worked in Biofilia to control the temperature in a fume hood. The turpentine was incredibly sticky, and we were nervous about it igniting, but the smells were lovely, evoking a pine forest. The turpentines deepened in hue and became more viscous as they were heated, and the cotton provided amber-like striations, as well as giving the gooey turpentine more structural integrity. The recipe suggests that once you have formed the mixture into balls that you leave it to dry in the sunshine for eight days before using it to make jewellery, but in the absence of Italian sunshine in Helsinki, we left it indoors. The “amber” remains a little sticky, but the colour and tone of both the Venetian Turpentine and the Canada Balsam is a convincing substitute for a piece of “true amber” purchased from a stone seller. The success of this recipe is perhaps unsurprising – “true amber” is fossilized resin, so the scent and appearance of heated turpentines would be very similar, and we can see structural similarities at a microscopic level.

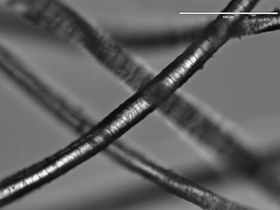

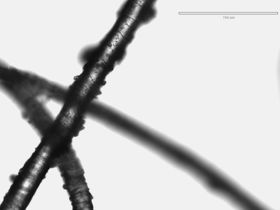

The fake leopard fur recipe also came from Ruscelli’s Secrets, this time the 1563 Italian edition. The dangerous ingredients – white lead and quicklime – meant we needed to work in the fume hood with PPE. After applying the mixture to rabbit fur and sheeps wool, we did not immediately see a change, but the next morning the spots had turned dark brown. We realized that the quicklime lye water helps to weaken the hair follicles of the fur and the white lead binds with sulphur in hair’s keratin to make lead sulphide, which is a black substance. You can see damage this permanent dye does to hairs under the microscope. While this recipe is quite destructive, few renaissance Europeans would have owned expensive and rare leopard fur, so perhaps it is no surprise that it would have been desirable to fake it. This workshop revised the negative associations we often hold for fictive or substitutive materials, by showing that fakes and imitations were highly esteemed by early modern makers and wearers.

Find out more on http://refashioningrenaissance.eu/ and see more of our experimental findings in our exhibition in Dipoli in September 2021.

Recipes

To make cleere stones of Amber:

Seeth Turpentine in a pan leaded, with a little cotton, stirring it until it be as thick as paste, and then pour it into what you will, and set it in the sun eight days, / and it will be clearer and hard enough. You may make of this little balls, haftes for knives, and many other things.

Girolamo Ruscelli, The secrets of Alexis: containing many excellent remedies against divers diseases, wounds, and other accidents, (translated by William Ward, 1595), part III, p. 251v-252r.

To make white hide with black spots the colour of a leopard or panther, and white hair black

Take one ounce litharge of silver, two ounces of quick lime, and in three ladles of water put [the ingredients] on the fire in a new pot so that it gets warm, then take it from the fire and with a wooden stick mix it; then take a brush and tint the white hide as it seems to you, one spot here and the other there, and according to the material make them thick, then dry it in the sun and when it's well dried, hit it with a rod and you will see dark spots tawny in colour. And if it is not well coloured in this way, you could tint it another time, giving the strikes where you did the first time, and the colour will become stronger and in this way you will have your intent. And this colour is always maintained and gives a good odour; and also putting the said material on hair or a beard will make it become roan and beautiful.

Girolamo Ruscelli, De'Secreti del reuerendo donno Alessio Piemontese prima parte, etc. (La seconda parte de i secreti di diuersi eccellentiss. huomini.-Parte terza.)(Venice: Antonio de gli Antonii, 1563), book II, p. 36v.

Refashioning the Renaissance is an ERC-funded project, based at Aalto University, which investigates how the popular classes engaged with fashionable clothing in the period 1550-1650. Few objects survive that were worn by the non-elites from this period, so we use a wide range of sources and methodologies, including hands-on experimental reconstruction, to make our research material and visible. With particular focus on Italy and Denmark, and additional research in Britain and Finland, the project studies what clothes were owned and worn by people who worked for a living in the early modern period. We are discovering that people like butchers, innkeepers, and tailors were able to participate in new fashions such as lace trims, silk ribbons, tailored garments, and jewelled accessories, as new materials and methods of making widened the market of affordable fashionable goods. The Refashioning project is led by Professor Paula Hohti Erichsen (Department of Art, Aalto), and the team is comprised of Sophie Pitman (Postdoctoral Research Fellow), Anne-Kristine Sindvald Larsen (PhD Candidate) and Piia Lempiäinen (Project Co-ordinator).

Interview with Refashioning the Renaissance Team

This interview is conducted with Sophie Pitman from Refashioning the Renaissance Team by Bilge Hasdemir as part of the Outre: Encounters with Non/living Things exhibition.

`Outré: Encounters with Non/living Things` online exhibition