How to Make High-Rise Construction Perform Better

The working group convened at Dipoli, in Otaniemi, on the 6th of March 2020. Seven presenters provided an overview of current high-rise construction technologies both in Finland and the USA. They also shared interesting examples from designed and completed projects.

Benchmarking with Californian High-Rise Projects

Builders in the USA have a long tradition of high-rise construction and are therefore a perfect benchmark for Finnish developers and contractors. Aalto researchers Ergo Pikas and Joonas Lehtovaara reported on their visit to California, where they’d met with local contractors.

From several interviews and site visits, Pikas and Lehtovaara learned about the strategies and practices of high-rise contractors in the USA. The researchers also received BIM models from a few projects for further analysis.

Although there are no developer-contractors in California as we have in Finland, on larger projects, the developer and GC always take part in a joint development phase. It’s important for the contractors to grasp the client’s business case because this determines the critical parameters of the project, including the feasibility of prefabrication. Volumetric construction could be beneficial in high-rise projects, but only if it is taken into account at the early stages of the process.

Pikas pointed out that the biggest risks pertaining to high-rise construction in California is in a potential sub-grade. For example, the soil could be contaminated with chemicals or even asbestos from previous buildings. Any unexpected delays have to be compensated for during the erection of the building frame.

Pinpointing the Differences

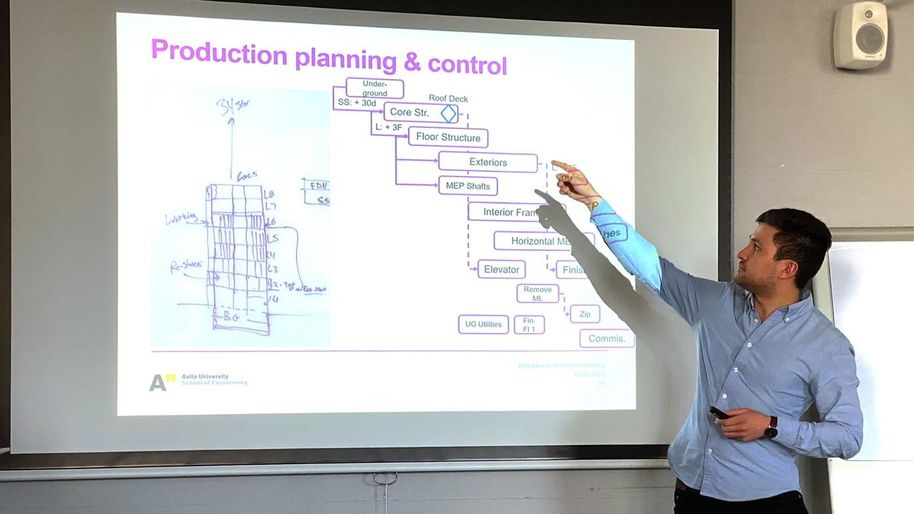

The researchers met with Suffolk and Skanska to learn from their production planning and control practices. It became evident that at least these two contractors did not practice Takt production in their high-rise projects, as we’re increasingly doing in Finland. Instead, they use the traditional critical path scheduling. They focus on five to six critical tasks and use buffers for the less critical activities. This often leads to a hustle at the end of the project as the workers have to catch up with the schedule.

Getting the interior elevators to work is critical in U.S. high-rise construction. Once it’s operational, the contractors can get rid of the man-lifts and start finishing the interiors.

A noticeable difference between Californian and Finnish high-rise construction is the extensive use of drywalls. Whereas Finns use concrete or brick walls, especially in residential construction, the Americans always use lighter drywalls, which speeds up the process considerably.

The main takeaway for Pikas and Lehtovaara was that in high-rise construction, the product and process have to be developed concurrently. You have to plan the whole production system holistically from planning to commissioning. In a project with a lot of repetition, a design or planning decision scales up and can make or break the client’s business case.

Joonas Lehikoinen, an Aalto student, is doing a special study that complements Pikas’s and Lehtovaara’s assignment. He’s collecting models of high-rise projects from the USA and Asia, and analyzing them in terms of costs, schedules, structural solutions and architectural characteristics.

High-Rise Logistics

Muge Tetik presented her research project on logistics at Loisto, a high-rise project in Helsinki. She will do this for her doctoral studies while working as an intern at Carinafour, a logistics company. The purpose of her research is to evaluate how logistics in a high-rise project differ from that in a low-rise equivalent and how the former could be improved. Previous research at Aalto University has provided her with plenty of information about logistics in low-rise projects. This also allows Tetik to make fact-based comparisons between the two project types.

On the Loisto site, Tetik is using Bluetooth beacons on a construction elevator and on selected workers to collect data about the movements of materials and workers on the site. One of the ways to assess the efficiency of logistics is to measure how long the workers have to wait for the buckhoists when they are moving materials. Tetik also interviews engineers who are in charge of the material logistics and representatives of the general contractor. In addition, she makes observations on the construction site.

Santeri Sompio of SRV, the developer-contractor of Loisto, explained how they are speeding up the on-site logistics. They use a Jumplift, a KONE product that is now being used in Finland for the first time. It has a mobile machine room that is moved up as more floors are built. In addition, SRV uses a large buckhoist to carry materials and a tower crane especially for the structural construction.

High-Rise Challenges

High-rise construction brings about new challenges for designers and builders. One of them is the stack effect. Also known as the chimney effect, which refers to the movement of air into and out of buildings as a result of air buoyancy. Ilari Ranta-aho, a Stack Effect Specialist at Ramboll, explained that the phenomenon starts having noticeable consequences once the building height exceeds 70 metres or 20 floors.

The stack effect can cause droughts and can increase energy consumption. It can also lead to problems at first floor entrance doors and elevator doors as they may not be able to be opened easily and may even start whistling. Furthermore, strong air flows can be detrimental to fire safety and smoke removal systems.

According to Ranta-aho, there are certain structural solutions that can be used to mitigate the problems from the stack effect. Revolving doors, drought lobbies, and the compartmentation of staircases and elevator lobbies are some of those tactics.

The Trigoni Project

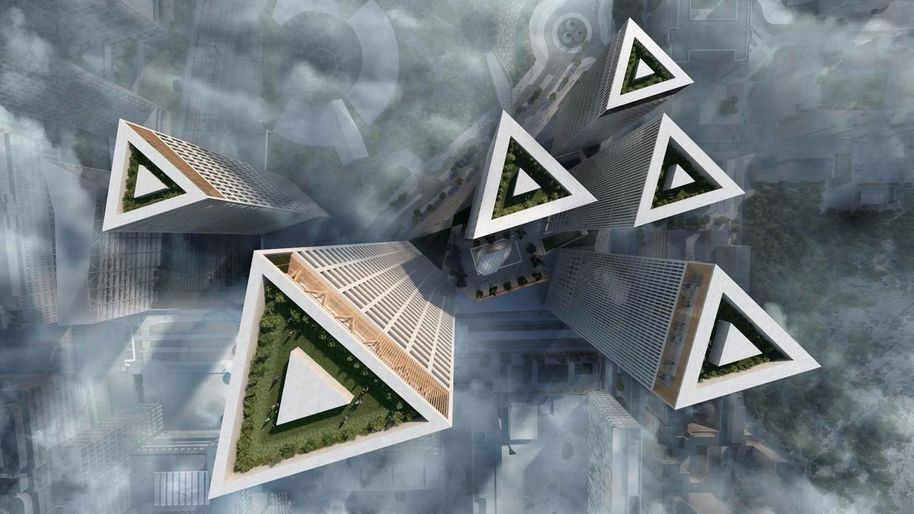

Mikko Moilanen, Head of Development and Innovation at Trigoni, a YIT high-rise project, concluded the event. The western part of the Trigoni project consists of five mixed-use towers with triangular footprints and a pedestal area. The highest tower will have 51 stories and reach a height of 180 metres. The construction of the towers is estimated to start in 2021-2022, after the completion of the city plan.

The distinctive triangular form of the towers is not purely an architectural choice; it has functional explanations as well. First of all, it will reduce the wind’s impact on the surroundings. Second, it provides good views from the apartments and offices. Third, almost all the sides of the buildings will get good lighting during the day. Finally, the forms, together with the other arrangements, will help reduce noise from the traffic surrounding the area.

The presentations induced a lively discussion in the working group. In future workshops, the group will continue to dig deeper especially into structural solutions for high-rise construction and will continue to garner ideas from projects around the globe.

Building 2030

The Building 2030 project envisions, researches and promotes a better future of construction.

Read more news

Physics Days 2026 gathered Finnish physicists to Aalto

The 2026 edition of the annual conference featured talks on moiré matter, women in physics and paper cuts.

Annual review looked back on the past year

The annual review of the School of Arts, Design and Architecture provided a comprehensive overview of the past year. Members of the community were also awarded in the event.

Alum of the Year Anna Brotkin: “We need modern stories about our era”

Screenwriter Anna Brotkin is the Alum of the Year 2026 of the School of Arts, Design and Architecture. She believes in the power of locality and the importance of hope in times of crisis.