Kuva kvasaarin suihkusta yllätti tähtitieteilijät

Tutkijat eivät ole koskaan aikaisemmin saaneet yhtä tarkkaa kuvaa näin kaukaisesta kohteesta.

This is the first time astronomers have been able to measure polarisation, a signature of magnetic fields, this close to the edge of a black hole. The observations are key to explaining how the M87 galaxy, located 55 million light-years away, is able to launch energetic jets from its core.

“We knew that there was a magnetic field around the black hole but we didn’t know much about it. Discovering the structure of the magnetic field so close to the edge of the black hole is a meaningful step forward”, says Senior Scientist Tuomas Savolainen of Aalto University Metsähovi Radio Observatory, a member of the EHT collaboration.

“We are now seeing the next crucial piece of evidence to understand how magnetic fields behave around black holes, and how activity in this very compact region of space can drive powerful jets that extend far beyond the galaxy,” says Monika Mościbrodzka, Coordinator of the EHT Polarimetry Working Group and Assistant Professor at Radboud Universiteit in the Netherlands.

On 10 April 2019, scientists released the first ever image of a black hole, revealing a bright ring-like structure with a dark central region — the black hole’s shadow. Since then, the EHT collaboration has delved deeper into the data on the supermassive object at the heart of the M87 galaxy collected in 2017. They have discovered that a significant fraction of the light around the M87 black hole is polarised.

“This work is a major milestone: the polarisation of light carries information that allows us to better understand the physics behind the image we saw in April 2019, which was not possible before,” explains Iván Martí-Vidal, also Coordinator of the EHT Polarimetry Working Group and GenT Distinguished Researcher at the Universitat de València, Spain. He adds that “unveiling this new polarised-light image required years of work due to the complex techniques involved in obtaining and analysing the data.”

Light becomes polarised when it goes through certain filters, like the lenses of polarised sunglasses, or when it is emitted in hot regions of space that are magnetised. In the same way polarised sunglasses help us see better by reducing reflections and glare from bright surfaces, astronomers can sharpen their vision of the region around the black hole by looking at how the light originating from there is polarised. Specifically, polarisation allows astronomers to map the magnetic field lines present at the inner edge of the black hole.

“The newly published polarised images are key to understanding how the magnetic field allows the black hole to 'eat' matter and launch powerful jets,” says EHT collaboration member Andrew Chael, a NASA Hubble Fellow at the Princeton Center for Theoretical Science and the Princeton Gravity Initiative in the USA.

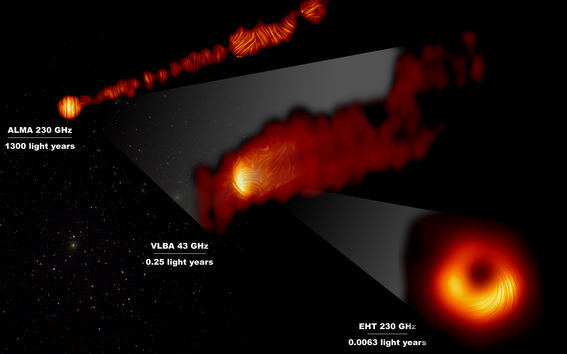

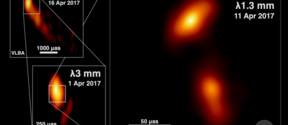

This composite image shows three views of the central region of the Messier 87 (M87) galaxy in polarised light. One of the polarised-light images, obtained with the Chile-based Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), shows part of the jet in polarised light, with a size of 6000 light years from the centre of the galaxy. The other polarised light images zoom in closer to the supermassive black hole: the middle view covers a region about one light year in size and was obtained with the National Radio Astronomy Observatory’s Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) in the US. The most zoomed-in view was obtained by linking eight telescopes around the world to create a virtual Earth-sized telescope, the Event Horizon Telescope or EHT. Credit: © EHT Collaboration; ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), Goddi et al.; VLBA (NRAO), Kravchenko et al.; J. C. Algaba, I. Martí-Vidal

The bright jets of energy and matter that emerge from M87’s core and extend at least 5000 light-years from its centre are one of the galaxy’s most mysterious and energetic features. Most matter lying close to the edge of a black hole falls in. However, some of the surrounding particles escape moments before capture and are blown far out into space in the form of jets.

Astronomers have relied on different models of how matter behaves near the black hole to better understand this process. But they still don’t know exactly how jets larger than the galaxy are launched from its central region, which is as small in size as the Solar System, nor how exactly matter falls into the black hole. With the new EHT image of the black hole and its shadow in polarised light, astronomers managed for the first time to look into the region just outside the black hole where this interplay between matter flowing in and being ejected out is happening.

The observations provide new information about the structure of the magnetic fields just outside the black hole. The team found that only theoretical models featuring strongly magnetised gas can explain what they are seeing at the event horizon.

“The observations suggest that the magnetic fields at the black hole’s edge are strong enough to push back on the hot gas and help it resist gravity’s pull. Only the gas that slips through the field can spiral inwards to the event horizon,” explains Jason Dexter, Assistant Professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, USA, and coordinator of the EHT Theory Working Group.

To observe the heart of the M87 galaxy, the collaboration linked eight telescopes around the world to create a virtual Earth-sized telescope, the EHT. The impressive resolution obtained with the EHT is equivalent to that needed to measure the length of a credit card on the surface of the Moon.

This setup allowed the team to directly observe the black hole shadow and the ring of light around it, with the new polarised-light image clearly showing that the ring is magnetised. The results are published today in two separate papers in The Astrophysical Journal Letters by the EHT collaboration. The research involved over 300 researchers from multiple organisations and universities worldwide.

"The EHT is making rapid advancements, with technological upgrades being done to the network and new observatories being added. We expect future EHT observations to reveal more accurately the magnetic field structure around the black hole and to tell us more about the physics of the hot gas in this region," concludes EHT collaboration member Jongho Park, an East Asian Core Observatories Association Fellow at the Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics in Taipei.

The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) collaboration, who produced the first ever image of a black hole released in 2019, has today a new view of the massive object at the centre of the Messier 87 (M87) galaxy: how it looks in polarised light. This is the first time astronomers have been able to measure polarisation, a signature of magnetic fields, this close to the edge of a black hole.

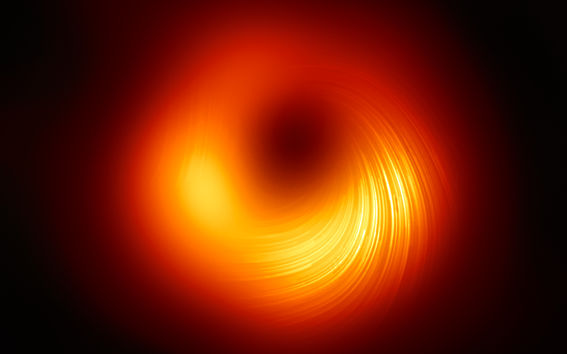

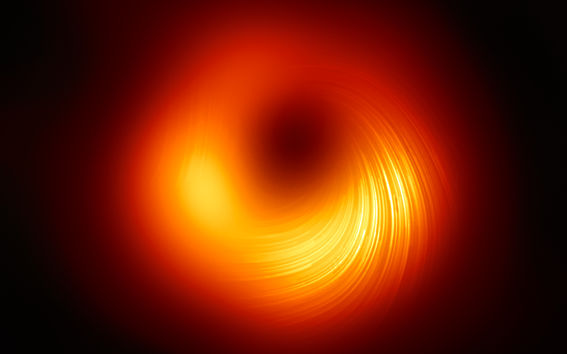

This image shows the polarised view of the black hole in M87. The lines mark the orientation of polarisation, which is related to the magnetic field around the shadow of the black hole.

Credit: EHT Collaboration

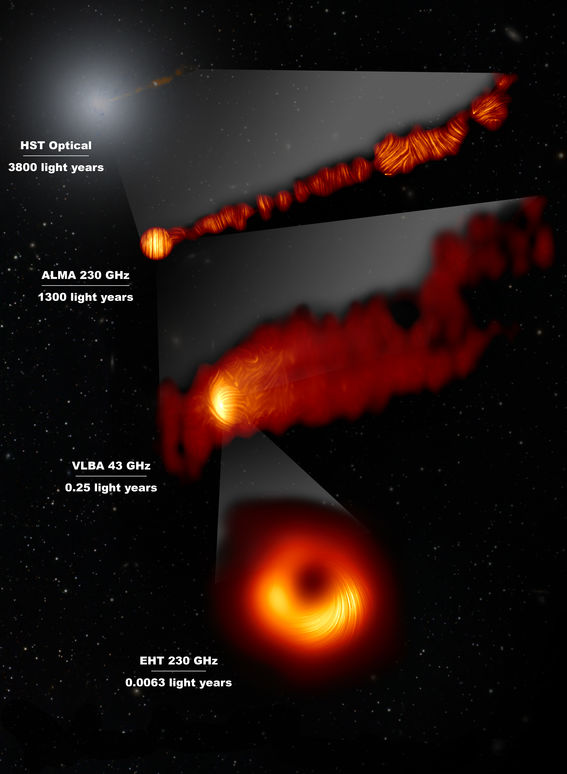

This composite image shows three views of the central region of the Messier 87 (M87) galaxy in polarised light and one view, in the visible wavelength, taken with the Hubble Space Telescope. The galaxy has a supermassive black hole at its centre and is famous for its jets, that extend far beyond the galaxy. The Hubble image at the top captures a part of the jet some 6000 light years in size. One of the polarised-light images, obtained with the Chile-based Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), shows part of the jet in polarised light, with a size of 6000 light years from the centre of the galaxy.

The other polarised light images zoom in closer to the supermassive black hole: the middle view covers a region about one light year in size and was obtained with the National Radio Astronomy Observatory’s Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) in the US. The most zoomed-in view was obtained by linking eight telescopes around the world to create a virtual Earth-sized telescope, the Event Horizon Telescope or EHT. This allows astronomers to see very close to the supermassive black hole, into the region where the jets are launched. The lines mark the orientation of polarisation, which is related to the magnetic field in the regions imaged.

The ALMA data provides a description of the magnetic field structure along the jet. Therefore the combined information from the EHT and ALMA allows astronomers to investigate the role of magnetic fields from the vicinity of the event horizon (as probed with the EHT on light-day scales) to far beyond the M87 galaxy along its powerful jets (as probed with ALMA on scales of thousand of light-years). The values in GHz refer to the frequencies of light at which the different observations were made. The horizontal lines show the scale (in light years) of each of the individual images.

Credit: © EHT Collaboration; ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), Goddi et al.; NASA, ESA and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA); VLBA (NRAO), Kravchenko et al.; J. C. Algaba, I. Martí-Vidal

Accepted papers:

Tutkijat eivät ole koskaan aikaisemmin saaneet yhtä tarkkaa kuvaa näin kaukaisesta kohteesta.

Aalto-yliopisto osallistui käänteentekeviin havaintoihin jättimäisestä mustasta aukosta Messier 87 -galaksin ytimessä.

Maata kiertävän radioteleskoopin havainnot ovat resoluutioltaan tarkimpia tähtitieteen historiassa; aivan kuin Kuusta voitaisiin katsella Maan pinnalla olevaa biljardipalloa.

Jättimäiset avaruuden syöverit voivat repiä tähtiä kappaleiksi – mutta myös muovata kokonaisten galaksien kehitystä.

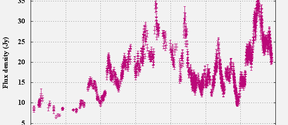

Metsähovin havaintojen perustana ovat aktiivisten galaksien radiosäteilyn korkeiden radiotaajuuksien pitkäaikaiset valokäyrät. 37 gigahertsin valokäyriä löytyy monesta kohteesta jo neljältä vuosikymmeneltä.