Studio Autumn: Capstone Project 2025: Adaptive Reuse in Downing Site, University of Cambridge, UK

Description:

This master-level studio course was arranged in collaboration with the University of Cambridge. There was supporting interaction also with the Finnish Institute in the UK and Ireland. The interaction with the Department of Architecture in Cambridge continued the Other Approach collaboration since 2022 which examines ways of living, communal living and living-related work. The Other Approach Project is the lens for seeing alternative ways of living. We have so far held two public architecture seminars (at the University of Cambridge in 2022 and in London at the Finnish Institute in 2023. There is also an important connection to the Urban Room programme of the Department of Architecture in Cambridge with themes of participation and inclusion, workshops, pop-up spaces, and co-creation.

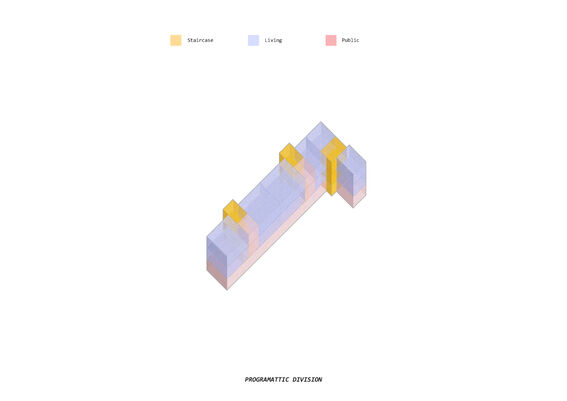

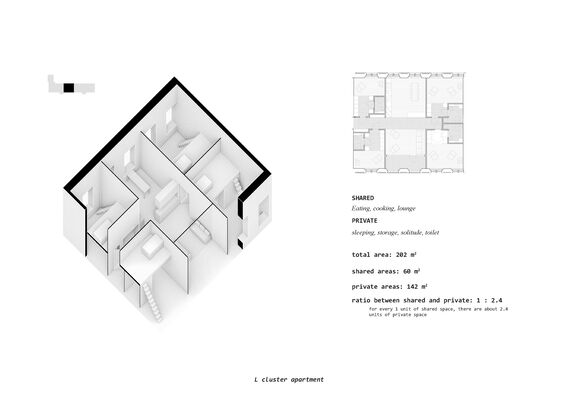

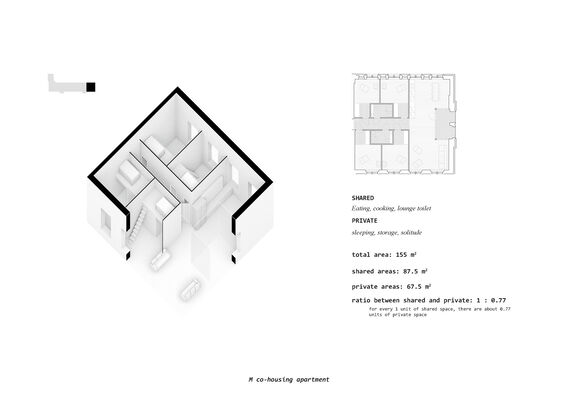

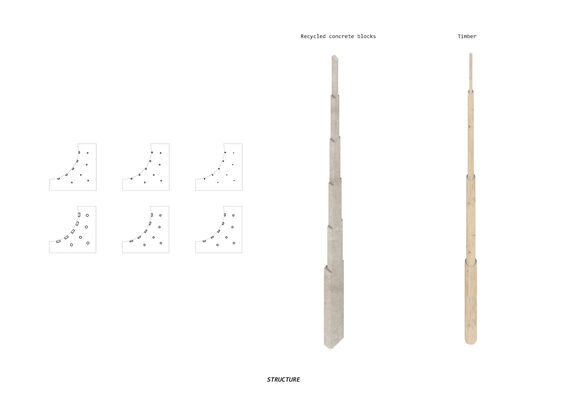

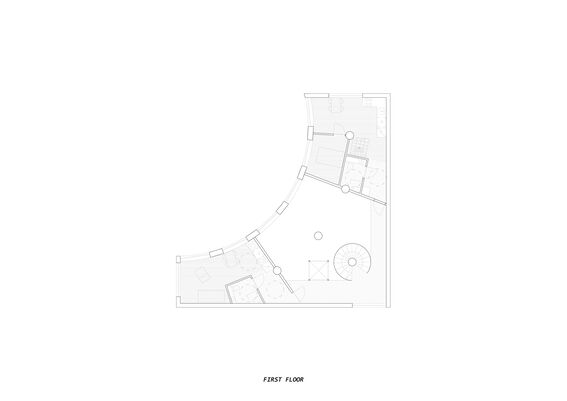

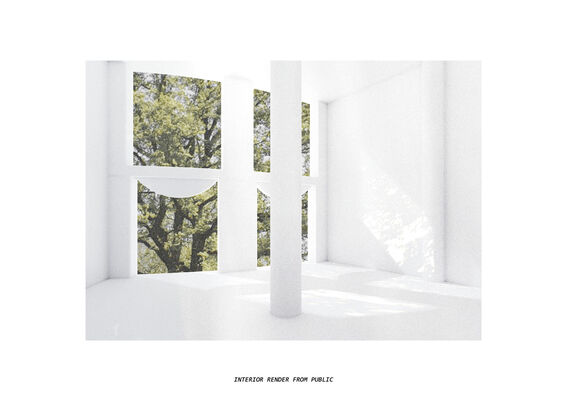

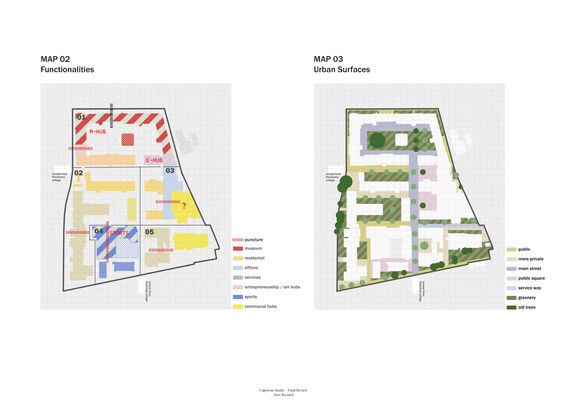

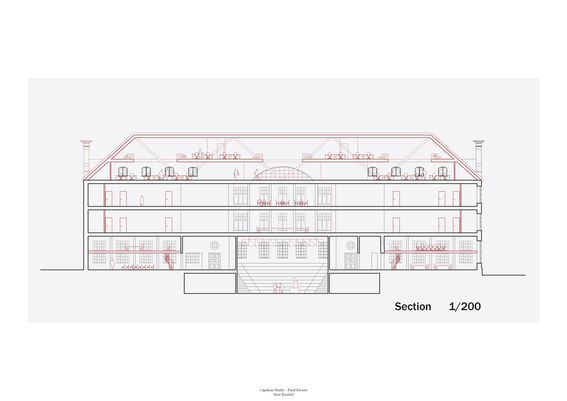

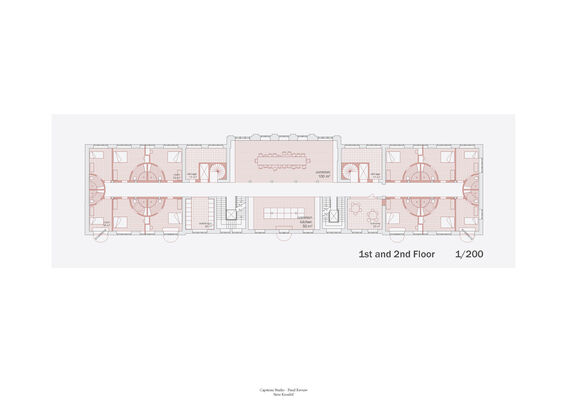

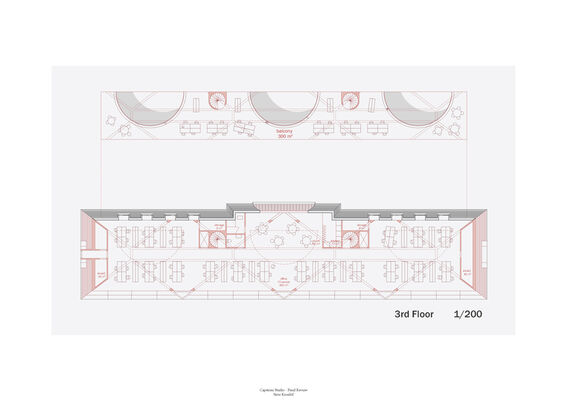

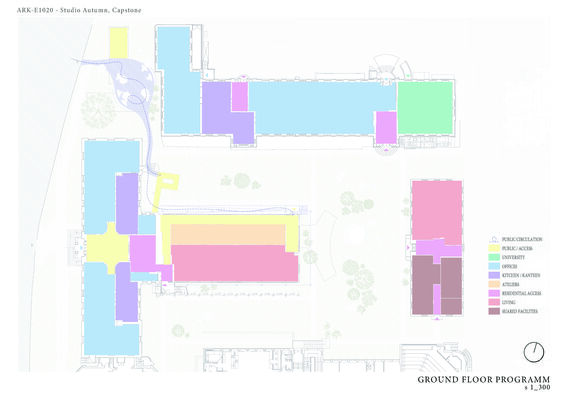

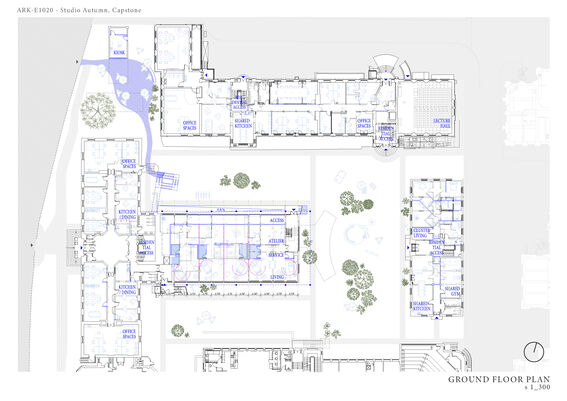

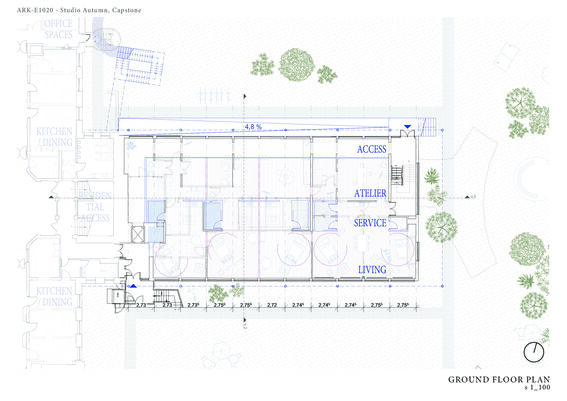

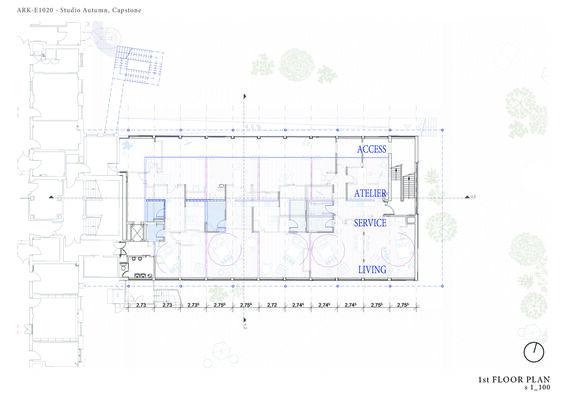

The themes of our project included urban renewal, adaptive reuse, social equality, co-housing, co-working, open city, social sustainability, and built heritage. We focussed specifically on reducing social differentiation and inequality, mixing activities, equality, co-living, communal workspaces related to housing and the sustainable reuse of buildings in the spirit of the circular economy. The project was centrally related to almost all of the UN's Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by combining societal and social effectiveness with the reduction of carbon dioxide emissions and energy consumption in the built environment through reuse.

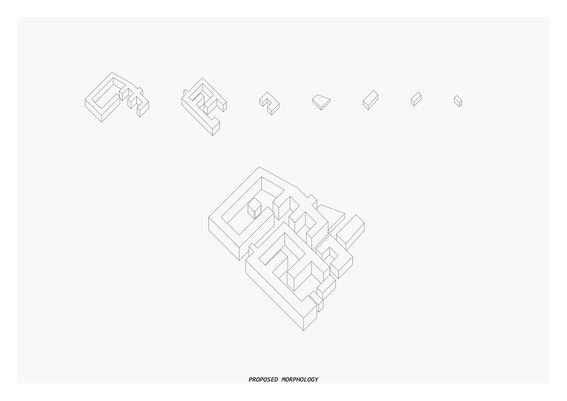

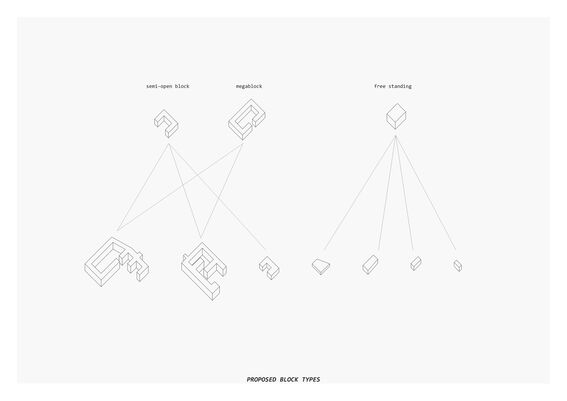

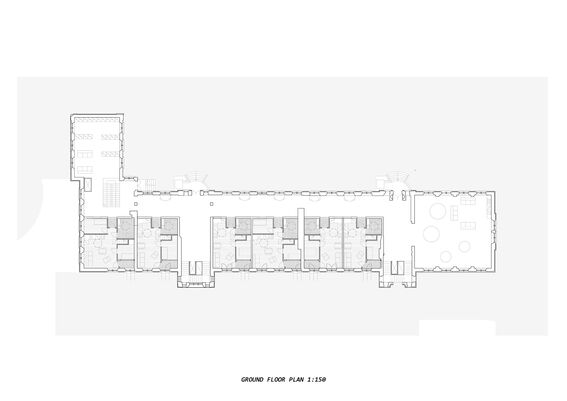

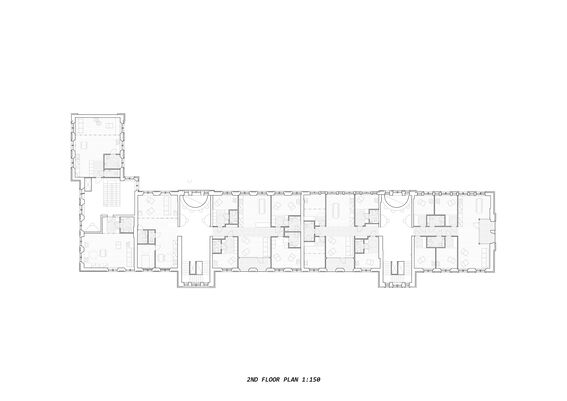

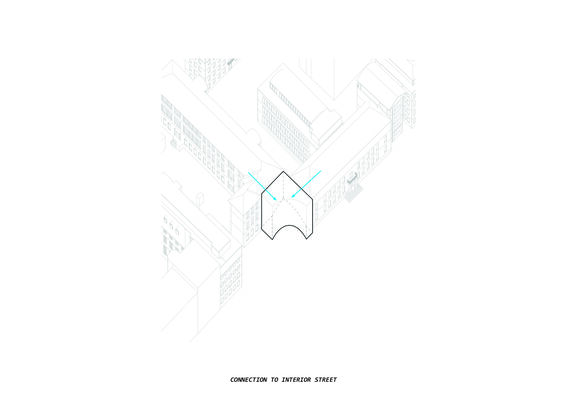

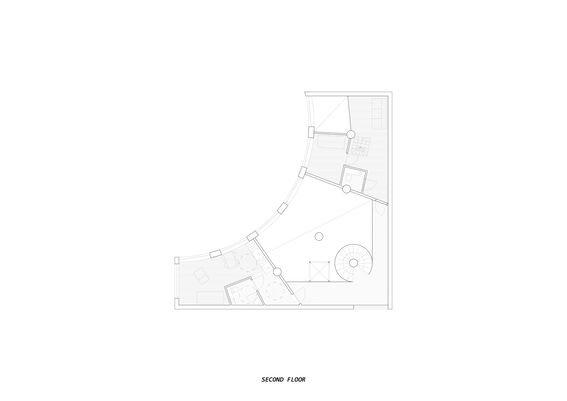

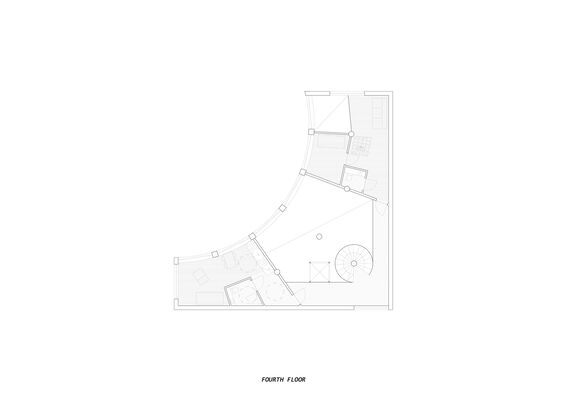

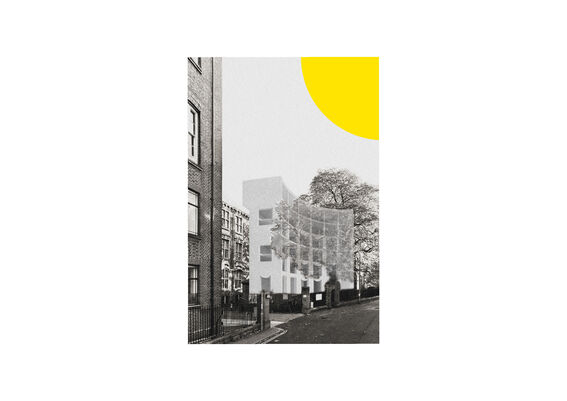

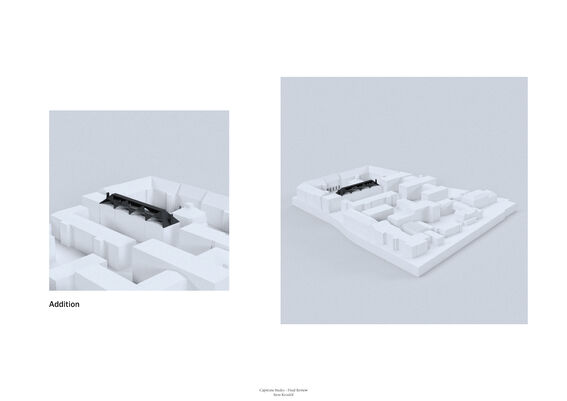

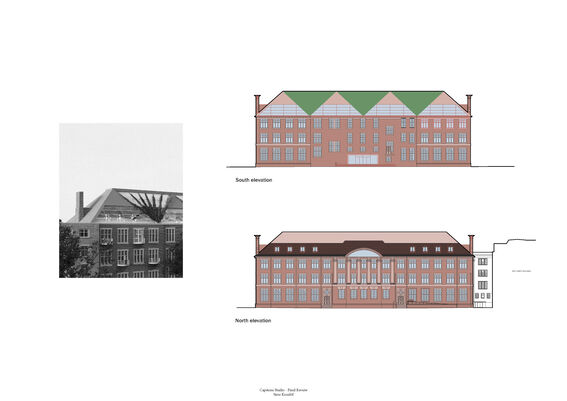

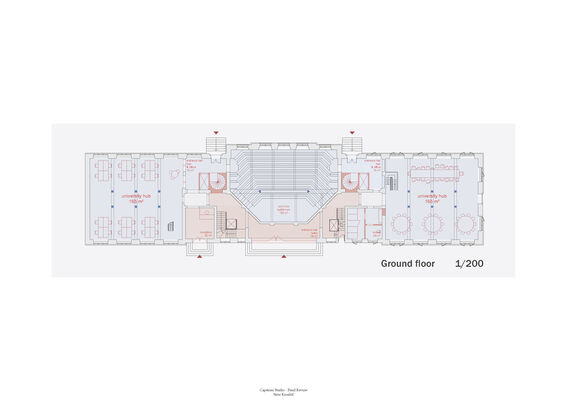

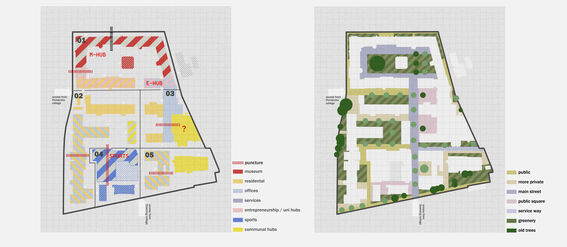

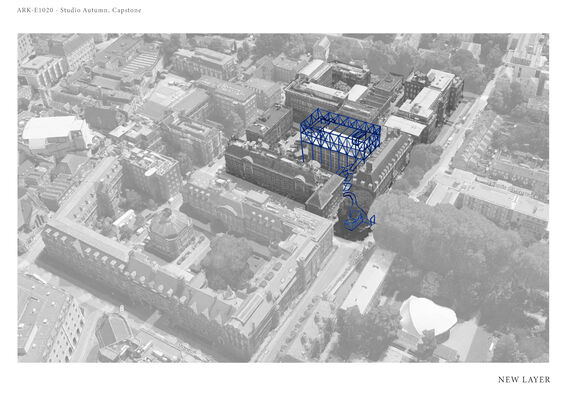

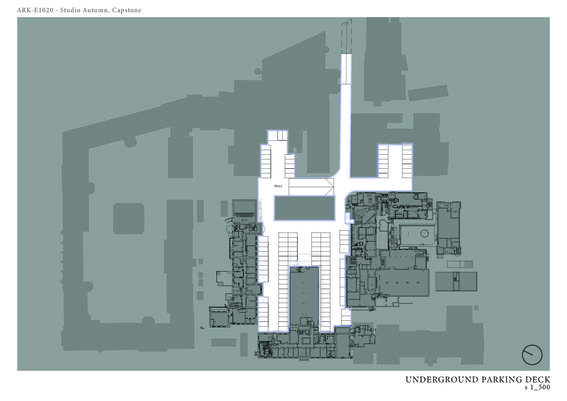

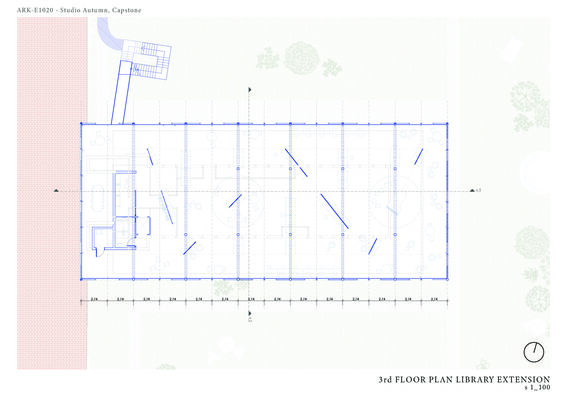

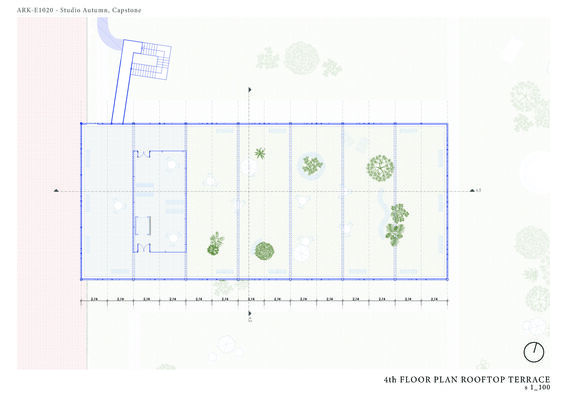

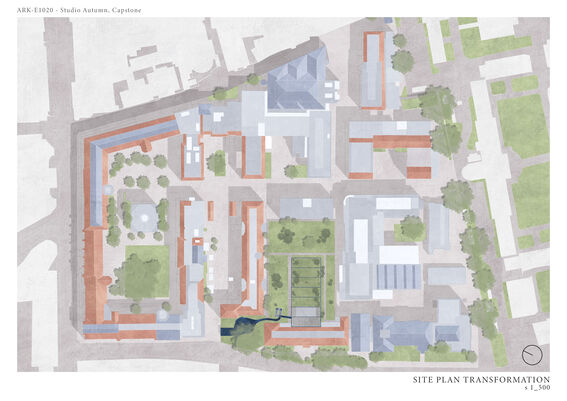

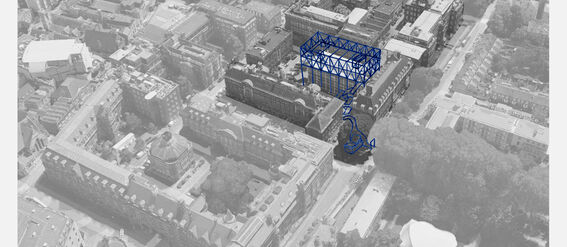

We experimented with sustainable live/work options for the design of the Downing Site in the centre of Cambridge. The site is owned by the University of Cambridge. The goal of the project was to produce plans for the reuse and additional construction of this historic area. The Downing Site is the original site of Cambridge University laboratories in the heart of the city. The north part of the area includes listed (protected) buildings and trees. The university has built a new laboratory area outside the city. The relocation of the research infrastructures from outdated and impractical facilities in the Downing area is ongoing, and the planning of the reuse of the old facilities is current. Due to the importance of the area, reuse should also be ambitious in terms of spatial programming and physical facilities.

The development of the Downing area into housing-oriented blocks would reduce the considerable social dichotomy in the centre of Cambridge between an elite university and a working-class city (the so-called "Town versus Gown" syndrome), diversify the demography of the centre and support the role of universities as pioneers in spatial planning. Our project also promotes social thinking and action, with which the circular economy and the reuse of buildings would become part of the values and lifestyles of the townspeople.

Teachers: Antti Ahlava & Karoliina Hartiala, with Sofia Nivarti from the University of Cambridge

Background

"Redefining what is ideal living includes the reconsideration of what is shared".

– Professor Antti Ahlava

The history of communal living

The tribal person lived communally. Plato’s Republic was communal. So was Thomas More’s Utopia and many of William Morris’ medievalist fantasies or Le Corbusier’s modernist ones. During the Middle Ages, communal living remained the typical household structure across most of Europe. Homes were essentially gathering places for small groups of revolving residents, representing a conceptual midpoint between hunter-gatherers’ living arrangements and stable premises. In addition to parents and their children, medieval households frequently included various townspeople, poor married couples, other people’s children, widows, orphans, unrelated elderly people, servants, boarders, long-term visitors, friends, and assorted relatives. People moved constantly among houses. “Home was the place that sheltered you at the moment, not the one special place associated with childhood or family of origin,” writes the historian John Gillis. Living with strangers was common, and locals would often treat houses like public property. It was often difficult to tell which family belonged where. In big as well as little houses, the constant traffic of people precluded the cozy home life we imagine to have existed in the past. In Sweden, the Iron Age long houses had several functions, which were gradually divided between separate buildings around in the Viking Age and the Early Middle Ages.

Compared to other areas of Europe, where the discussion about the social life in the villages is often focused on the feudalistic relations between peasants and the elite landowners, in Sweden and Finland the discussion has more often been centred around the relationships within the villages or the rural peasant community. The agency was not reserved only for ruling elites or the head of a peasant household but all those who lived in the villages.

It wasn’t until the 1800s that divisions were drawn between who would live with whom, and towards the end of the 19th century the so-called “godly family” started to take shape, that of single families living in individual homes. Industrialisation made extended communities less necessary and communal living was mostly lost. The 1920's Svoboda Hof and Karl Marx Hof in Vienna had housing combined with all needed services in shared form.

The 1930's Isokon Flats in London had very small kitchens as there was a communal kitchen for the preparation of meals. Services, such as laundry and shoe-polishing, were provided on site. Another 30's communal housing building in London, Kensal House, has a central community room, fostering social interaction among residents. The co-housing concept spread in the 70’S from Denmark to several other countries, and countries like Sweden adopted it with full force, even introducing a number of state-owned co-housing buildings with hundreds of residents. Splitting cooking, childcare, and household expenses can save lots of time and money. For these reasons and others, Danish and Swedish governments have long supported co-housing.

Contemporary communal living has spatial and programmatic social support structures to encourage social interaction in neighbourhoods. Co-living enhances social interactions and thus encourages the growth of local social capital. Britain’s co-living developments are more advanced than in Finland and one can juxtapose such producers as historical Isokon and Kensal House, and the contemporary Town and K1, the real estate company Collective compared with Finnish inventive sustainable developments of packaging obsolete office spaces and new housing as communal living Duaali homes by helsinkizürich.

Live/work arrangements

In ancient and medieval cities, live/work arrangements were the norm. Artisans, merchants, and tradespeople commonly lived above or behind their workshops or stores. Urban blocks were dense, multifunctional, and integrated. The home was not separated from economic activity. A medieval craft master’s household integrated work and family life. The front of the house was often the workshop; sales took place in that room or at a market stall nearby. The bulk of most craftsmen’s wealth was in their tools and supplies, which were stored in the workshop or in small cellars or outside sheds. The craftsman’s family included not only biological relatives but also those bound to him under long-term work contracts.

Early industrial buildings turned the medieval model upside down: the machine operators lived on ground floors and worked above on a floor from where their spinning machines were connected to outside sources of energy – very often watermills on the courtyards or beside the buildings. Modernist planners (e.g., Le Corbusier) advocated for the strict separation of functions – living, working, recreation, and mobility. The functionalist city became dominant in urban planning, suppressing live/work combinations. Live/work spaces are today central to discussions of urban resilience, sustainability, and affordability. They support an integrated, human-scaled urban life. Could the 15 min city become a 5-min city?